The Original Post:

(This post originally appeared on the Stitches Magazine Blog, On Links and Needles, Monday, March 29, 2010. In recent days, I’ve been answering questions about how we learn embroidery, why I share so much information, and why I am a proponent of openly teaching technique, and this no-longer-available post seemed germane. -EC)

“Bernard of Chartres used to compare us to dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants. He pointed out that we see more and farther than our predecessors, not because we have keener vision or greater height, but because we are lifted up and borne aloft on their gigantic stature”

John of Salisbury, Metalogicon, 1159

So why have I dragged us through a 12th-century quote, and what does it have to do with embroidery digitizing? If you are struggling with concepts that you know you’ve seen handled before, it may mean everything.

We’ve all heard the phrase to which my title alludes. Scientists are fond of dragging it out for any presentation on a new discovery, perhaps cognizant that they must thank their predecessors as they would like to be thanked when the great minds of the future expand on their discoveries. It was famously paraphrased by Isaac Newton, but I’m much more fond of John’s version, as it captures so eloquently the heart of my message to you today: To be a great digitizer, learn from those who have come before you. Now I know that you’ve heard this from me before, but this post is different. This time I’m going to (briefly) teach you just how to go about it.

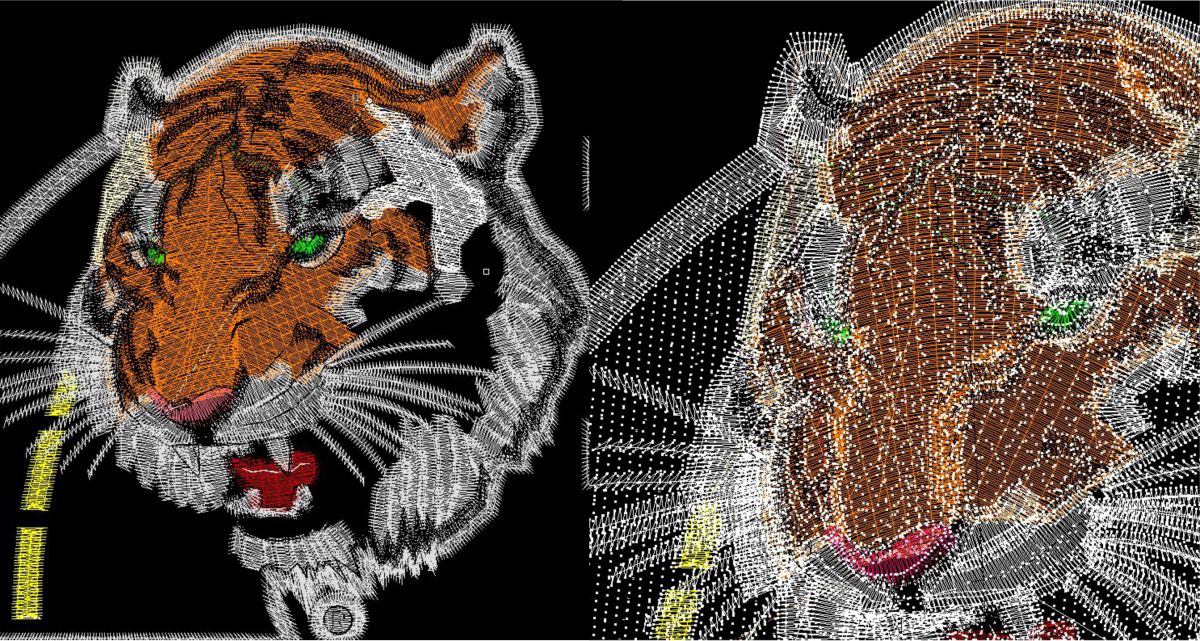

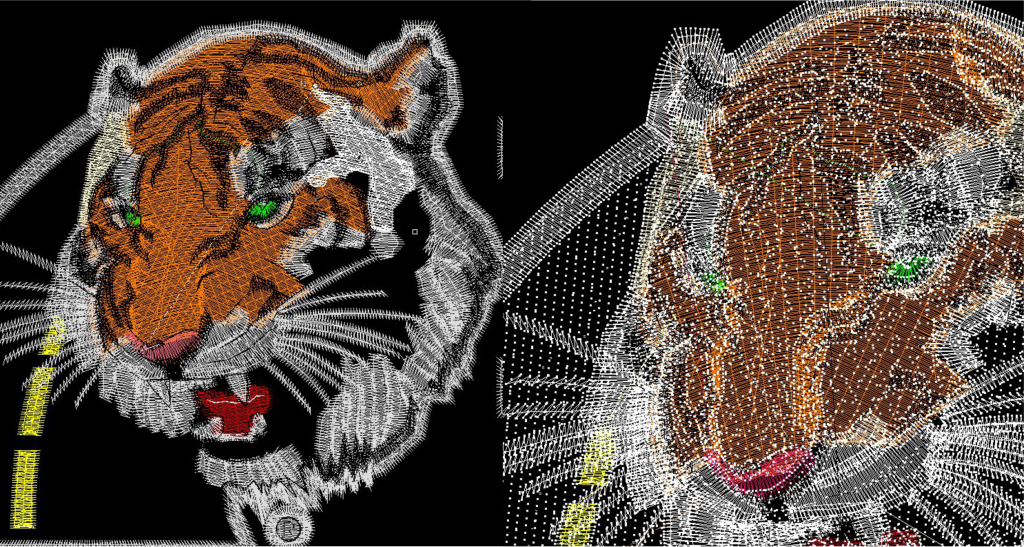

If we, as digitizers, have done our due time as operators or have at the very least run samples, we are familiar with the fact that watching a well-digitized design run opens you up to a world of information on maintaining the proper sequence of elements, managing push and pull, the effect of different stitch angles, and much, much more. This is most certainly the first step to learning from the masters; when you find a good digitizer, buy their stock and watch it run. Though it is best done on a machine, watching it run repeatedly via the redraw feature on your digitizing software will do in a pinch, though it won’t replace seeing the stitches interact with the substrate. Watch the design. Make notes. Repeat. Keep a file of the best designs, or designs that have techniques you want to master. Then we’ll be ready for the next step.

I know what you are thinking: “How does this translate to digitizing? I can watch and make notes, but when it comes to making my own design, how do I know what settings to use?” This is where modern technology is going to open up a universe of possibilities to you. So, you have that file of designs I told you to keep, right? Load up your favorite one so it is sitting there on-screen in your digitizing software. Now get out your pad and pen. If you’ve been reading this blog a while I’ve told you that you are sculptors, salesmen and even teenagers on a mall frenzy – well today we are going to become scientists.

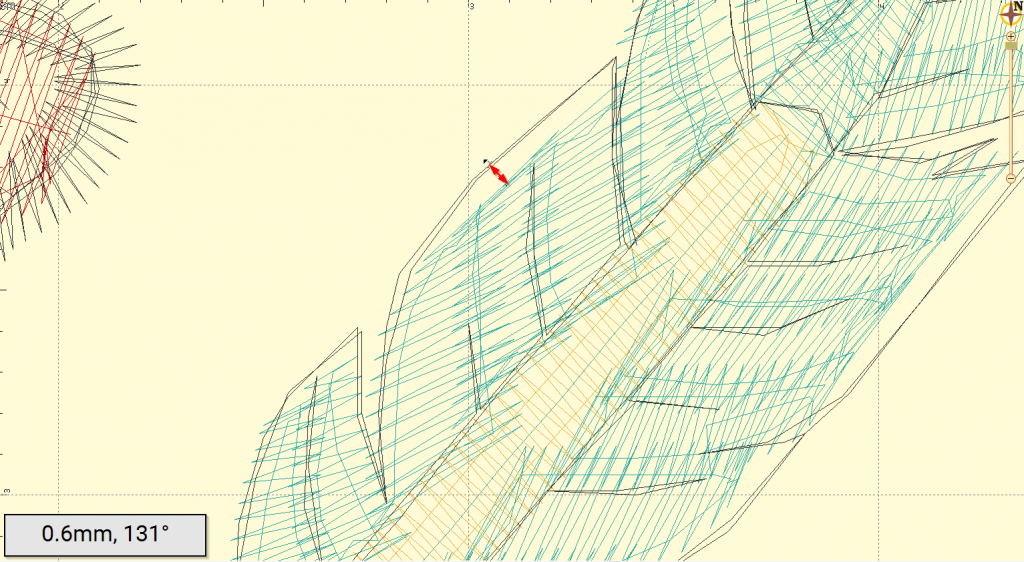

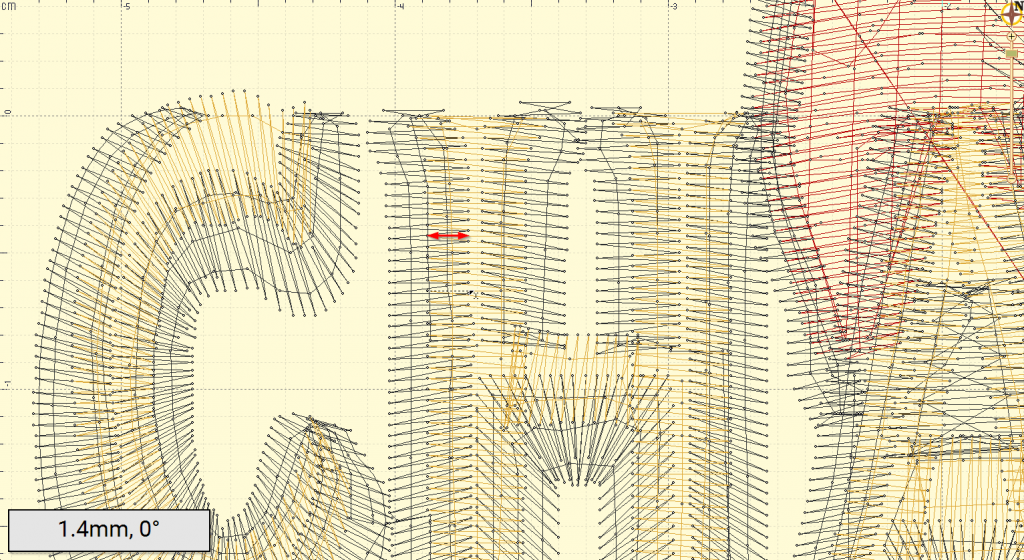

Your digitizing software almost assuredly has a little tool for which there is a ruler as an icon. This is your measuring tool, and with it you are going to unlock the minds of your mentors. Start measuring! With a simple click and drag, the ruler tool will allow you to measure any value you could want to know. Measure along any stitch to know its length, whether a simple straight stitch or merely one in rows upon rows of tatami fill. Measure the width of your satin stitches. Look carefully at the amount of distortion between a border and a fill. Measure that gap. Look at how much overlap there is from one section to another on two segments that mesh well, and measure that too. Measure between two horizontal lines in a satin stitch or over three in a fill – there is your density (a measurement of space between rows of stitching, really).Every measurement you make reveals the solution to another mystery. Write it all down with your observations from running the design, and your understanding will increase.

Now we really must have a complete stitch-out for the final stage of our study. Look at your measurements for satin stitches, look at your distortion measurements, and start to compare them to the real thing. Take out a reliable ruler and see how the width of satin stitches has reduced; see how they have pushed toward their open ends and how borders and filled elements interact. Write down everything you find that differs from the file to the stitch-out. Now you are armed with the knowledge of how much wider a satin stitch must be on-screen to be a certain width on your substrate, how much it will push to the ends, how each stitch will move and deform the particular substrate on which you are running.

It’s time to ascend to those shoulders and look out on this new vista. Translate those measurements to actions! Make new fill values with the stitch lengths and densities used in your masterwork. Expand your satins to account for the distortion levels in the master design. Try the angles and stitch types you observed. Express yourself with these new tools, and develop new techniques based on what you learned. With enough study, diligent practice and your own trial-and-error discoveries, you may be the giant turned step-stool for the next generation of digitizers.

Updated Thoughts and Context

Those who have followed any part of what I share have heard me carry on about ‘design analysis’, ‘retail research’, and how to study embroidery with the idea of learning, recreating, and remixing what we see. Though I will never advocate or bear ‘knocking off’ the creative design work of other digitizers, I’ve always thought that the basic techniques and the nature of our medium as machine embroiderers should never be hidden behind the defense of ‘industry secrets’. To this point, I’ve spent almost the entirety of my career writing, teaching, sharing, and releasing my work into the community, encouraging the dismantling and reconstruction of those works.

To my mind, when we are at our best, we are collaboratively working toward the betterment of our craft, leaving a legacy of technique and teaching to keep the love of the stitch alive far beyond our own time and contexts. I’ll always defend the right to make a living with your art, but I encourage everyone to examine the difference between the natural developments of technique which owe not only to our machine embroidery elders, but to those who in the dim depths of history plied needle and thread by hand, and the individual creative efforts of design that deserve some time to feed the living artists who created them. For every learner who reads this, if you give credit where it’s due, give back when you begin to create, and do your best to be a good steward for embroidery, I’ll be happy if my shoulders were broad enough to boost you up.

LEAVE A COMMENT